At 17, literature claimed me. The stunning effect of understanding some of King Lear and the heady influence of a teacher who was a devotee of DH Lawrence (think Robin Williams in Dead Poets Society) switched me on to literature and poetry and I have never wanted my life to be about anything else.

From studying to teaching and finally to writing, literature has been my passion and this is the story of how the women surrealists ended up being the inspiration for my first novel.

I discover feminist literary criticism

It was in the late 1980s that I encountered the feminist critique of the literary canon. My undergraduate degree in literature had begun with Geoffrey Chaucer and ended with Frank O’Hara and I had not even noticed the lack of female representation on the syllabus. Neither did I realise that questions of women’s lives were ignored rather than included in the universal values of literature.

Feminist criticism as I encountered it, via my postgraduate studies and discussions in a women’s reading group, was not an aggressive tirade against male oppression but instead a joyful, inspiring and thrilling series of discoveries of exciting, life-enhancing new writers writing about subjects never touched on by the male ‘Greats’.

I picked the then little-known poet H.D. (Hilda Doolittle) to study. This led to an eclectic acquaintance with feminist academics, poets and visual artists who gathered in Cornwall each summer for a week to talk about her life and work.

I begin to teach

Back home, I was fired up and proposed teaching a course on women writers at my university’s extra-mural department. The head of department, a kind but very traditional man, was puzzled by the idea but allowed me to run the course with the proviso that men were not excluded from taking it. So I began my long, happy and appallingly-paid career of creating courses on literature and feminist theory that were accessible to people with no academic background. I taught in church halls and library back rooms and did much of the publicity myself.

Soon after these courses were established and running in different parts of North Wales there was a proposal to set up a postgraduate degree in Women’s Studies. A lecturer from the English Department was earmarked to teach the literature module and, uncharacteristically for me, I stepped up and asserted myself. ‘I’m the one to run that,’ I said, and so it was agreed. I upgraded my community courses and we began the extraordinary project of taking mature women with first degrees in various subjects or professional experience at a high level and exposing them to feminist ideas as part of a group.

The heady effects of consciousness-raising from the 1970s were played out again in North Wales through the late 1990s and 2000s. Women who were meek became bold, women who were married became divorced, women who were homophobic had crushes on other women, women who were housewives began careers and some women who already had careers got management roles. There were marriages, babies and friendships for life. No one was unchanged.

Feminism and the arts

I decided to study for a doctorate and went back to H.D., this time to look at the influence of cinema on her work. Soon after I gained my Ph.D., I was appointed to run the Women Studies MA.

The reason I chose film as my research topic, and was confident enough to do so, was a result of teaching Women’s Studies. On top of the literature course, I had developed one on women in the arts which ranged across fine art, film, music and media: any discipline, in fact, with feminist criticism written about it.

I had discovered that the basic approach of feminist literary criticism (who are the forgotten women? how is their work influenced by women in the past and how have they in turn influenced subsequent writers? is their work different in style or content to men’s equivalent styles or genres?) can be and had been applied to all sorts of other cultural forms and artefacts. I granted myself permission to study and teach unfamiliar subjects such as films noir of the 1940s and Mills and Boon romances.

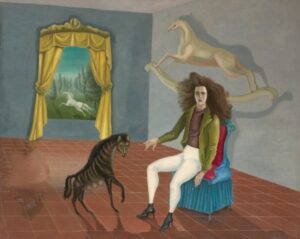

I also ranged far and wide into visual art, and this is when the women surrealists entered my life. They continue to obsess me to this day with their bold, dreamlike, inspiring work that combines self-exploration and the inner world of the unconscious with visually arresting stories and images. I find them both accessible and endlessly mysterious.

The women surrealists

I can’t remember what names or works I knew of surrealism at the time I first discovered the women surrealists, but I assume it was the usual restricted knowledge of Dali’s melting watches and Magritte’s man-with-his-face-obscured-by-an-apple. The existence of Leonora Carrington, Dorothea Tanning and Meret Oppenheim as well as Frida Kahlo, who was the only one getting exposure at the time, hit me with the same force as Alice Walker, Toni Morrison and Angela Carter had done when I first encountered feminist literature.

The more I read about their lives, their narratives of escape, struggle and descent into obscurity, the more I wanted to tell their stories. So I decided to write a novel about the women surrealists. And now, in 2024, I am preparing to publish it.

Next time: the ups and downs of writing and submitting my first novel.

Loved reading about your journey.

Thank you so much, Wanda.

What an amazing adventure and voyage of discovery you have been on Kathy – one of enlightenment and purpose – one beneficial to others as well as yourself. I am in awe of your achievements; and inspired by your dedication, focus and investment in female studies in the creative arts. I look forward to reading your first novel. Many congratulations!!

Thanks, Debbie! Yes, it’s been a long journey, but hugely fulfilling.