Swimming with Tigers is based on real historical figures associated with the surrealist movement in the 1930s. When I first started to plan my novel, I was all set to fictionalise the life of one particular surrealist: Leonora Carrington, whose life-story already reads like a novel.

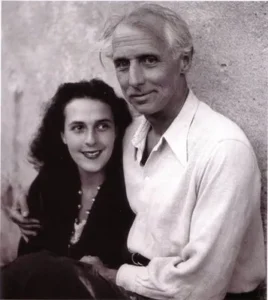

Leonora Carrington

Carrington was born in Lancashire and her father was a wealthy industrialist with high social ambitions. She was presented at court as a debutante but rebelled against every part of her upbringing except the Irish fairy stories told to her by her mother and nanny.

Carrington was born in Lancashire and her father was a wealthy industrialist with high social ambitions. She was presented at court as a debutante but rebelled against every part of her upbringing except the Irish fairy stories told to her by her mother and nanny.

In 1937, aged 20, she ran away to Paris to join the artist Max Ernst (then aged 46) and the other surrealists. Her family disowned her. When Max, a German, was imprisoned as an enemy alien in 1940, she made the journey to Spain but ended up incarcerated herself in a mental facility that used convulsive drugs as a treatment. She escaped again, and in Lisbon arranged a marriage to a Mexican diplomat.

This period of trauma is recorded in a book called Down Below and the straight-jacketed figure in the painting Green Tea from 1942 might well be a reference to her confinement at the sanatorium in Santander.

She left Europe in 1942 and went to the U.S., then the following year settled in Mexico City, becoming close friends with the Spanish surrealist Remedios Varo. After becoming involved in radical politics following the student protests in the 1960s, she had to leave Mexico for her own safety and eked out a living in New York for many years before returning to Mexico City for the rest of her long life.

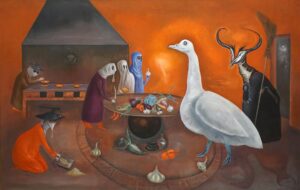

Her artwork often combined Mexican motifs with the Irish fairy stories from her childhood.

She died in 2011.

I was particularly fascinated by Leonora’s arrival in Paris at the height of the surrealist revolution in art in the late 1930s and the terrible impact of the outbreak of war. I wanted my reader to feel the exhilaration of a young woman breaking free of the social expectations of good behaviour and escaping her destiny as merely a wife and mother by joining a vibrant art movement but also to experience the infantilisation of the child-woman role assigned to women by surrealist ideals and being excluded from the ‘men’s club’ of the surrealist inner circle.

A composite character

In the end, I decided not to merely fictionalise Leonora’s life but to make a composite character from a number of women surrealists.

I gave myself total license to combine more than one woman’s life into a single figure and to invent works of art based on real surrealist art.

Using some of Carrington’s life, I mixed in elements of Meret Oppenheim, Eileen Agar, Ithell Colquhoun and Lee Miller to create a new fictional character, and called her Penelope Furr.

I gleefully described my fictitious Penelope as she made real works of art such as Meret Oppenheim’s notorious 1936 Object (fur covered cup and saucer).

Penelope also makes the Angel of Anarchy which was, in reality, created by the English surrealist Eileen Agar.

The novel follows Penelope’s joyful arrival in Paris to become a part of the surrealist group, her struggles to gain equality as a woman and her transformative friendship with the other main female character in the book, Suzanne.

The male lead(s)

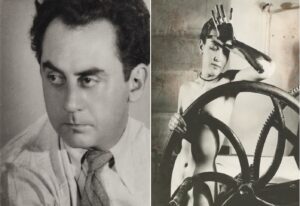

The main male character in my novel is similarly a mixture of more than one real-life surrealist: Penelope’s lover Rolf has elements of Max Ernst and Man Ray.

Rolf is taken away in 1940 as was Ernst and he creates some of Ernst’s art such as Two Children Threatened by a Nightingale, but Rolf is also a pioneering photographer and photographs Penelope next to a printing press as Man Ray photographed Meret Oppenheim in Veiled Erotic.

Penelope accidentally discovers the technique of solarisation in Rolf’s darkroom in the same way as Lee Miller did when living with Man Ray: she thought a mouse had run over her foot and put the light on, briefly, during the developing process, leading Man Ray to establish his trademark dark silhouette effect.

Some characters are more or less drawn 1-to-1 from life. For instance, the self-proclaimed leader of the surrealist movement, André Breton,  appears in the novel as Louis D’Argent. In general, I have tried to be fair and unbiased towards the men of the surrealist movement, who were after all, men of their time and by those standards, very liberal in their views about women but for the character of D’Argent, I have drawn out Breton’s less positive traits: homophobia, dismissal of women’s creative potential and all-round pomposity. I had some qualms about this as I am an admirer of Breton but, for dramatic purposes, I needed to show just what the women in the surrealist movement were up against.

appears in the novel as Louis D’Argent. In general, I have tried to be fair and unbiased towards the men of the surrealist movement, who were after all, men of their time and by those standards, very liberal in their views about women but for the character of D’Argent, I have drawn out Breton’s less positive traits: homophobia, dismissal of women’s creative potential and all-round pomposity. I had some qualms about this as I am an admirer of Breton but, for dramatic purposes, I needed to show just what the women in the surrealist movement were up against.

An intriguing figure brought to life

Suzanne, my second main female character, came directly from a book by André Breton.

In 1928 Breton wrote about meeting a strange, visionary young woman on the street in Paris one day and how her intuitive, spontaneous behaviour became for him the original surrealist blueprint of how to live.

Nadja was for a long time thought to be fictitious but now more is known about her, including her full name: Léona Delcourt. The real Nadja was taken to a locked asylum in 1928 and died in 1941, possibly of starvation.

There was a rumour circulating in the 1970s, however, that she was still alive and had been seen in France.

This mysterious figure seemed to me to cry out to be put into a novel and I arranged for her to escape from incarceration, meet Penelope and go on to have a longer life.

However, one of the epigraphs to my novel is from a remark made by Nadja on the phone: “I cannot be reached” and in this way I acknowledge that the real Nadja can never be known fully.

A checklist

The freedom I gave myself to alter, borrow or steal from the surrealists and their work, and indeed to invent surrealist paintings and objects myself, was a delight during the writing of the novel. As I moved towards publication, however, my old habits as a teacher reasserted themselves and I felt compelled to provide a glossary or guide to the real art and artists on which the novel was based. So, at the end of the book, I have added an Author’s Note detailing where my fiction has diverged from fact.

Figuring out what was real from what I had made up was not always easy! I spent some hours scouring my reference books and the web to find out who had made the bathing cap with snail shells before realising that I had invented this surrealist artwork myself! In the end I left it out of the novel but maybe one of you artists reading this blog could make it for me?

I hope that learning a bit about the real historical figures behind the book has made it more interesting. My overriding aim has always been to promote the women surrealists and make their names and work better known so I hope that my readers will go off and find out more about the real women when they have finished reading the story that I have made up.

Thanks Kathy… nice to have a bit more background and info. David hadn’t seen the ManRay photo before … but fortunately cannot replicate it as my press doesn’t have a wheel I could hide behind.